Rudi heaves on a long lever. The trunk of ash, balanced between two iron trolleys that run on rails, judders forward. Inch by inch, it rumbles towards a set of seven, vertical blades. Rudi shouts over the din as he makes adjustments; he must ensure everything is aligned perfectly. Satisfied with the trunk’s trajectory, he pulls a second lever.

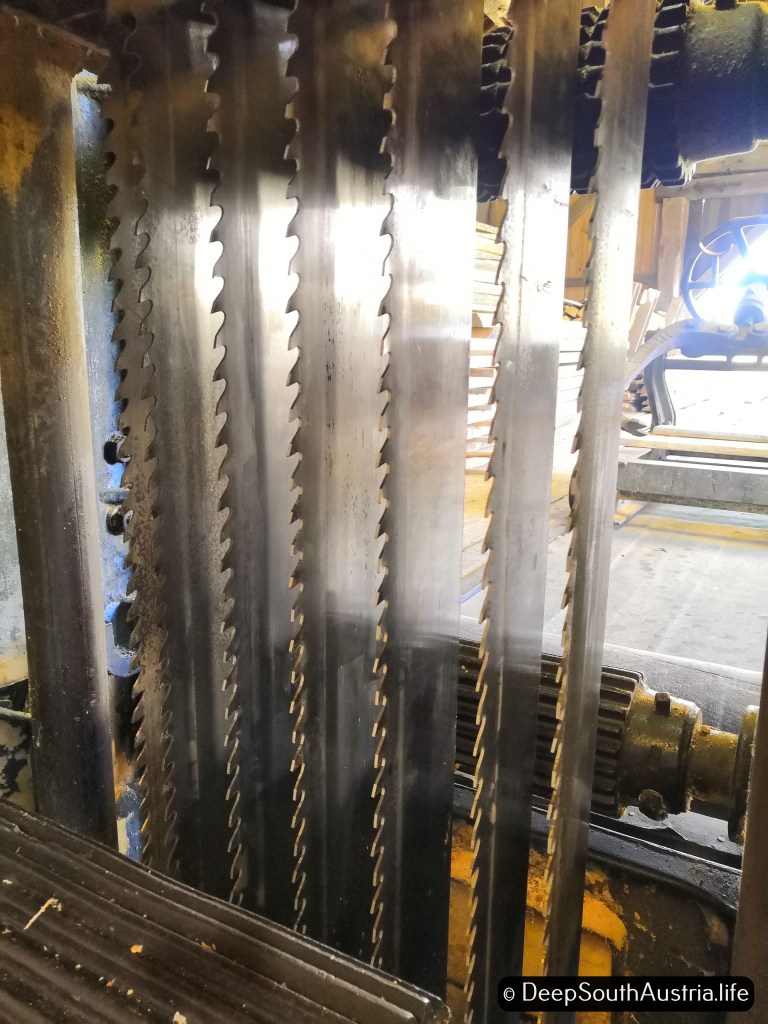

The saws start oscillating. Slow at first, they get faster and faster and faster, until they become a metallic blur. The trunk – gripped by two mighty, spiked cogs – is pulled towards a mouth of menacing teeth.

Finally they bite. There’s a wonderful sound as metal meets wood. Sawdust spurts high into the air like popped Champagne, then floats to the floor like snow. This is sawmilling: old school.

The Valley of Lost Waterwheels

I was at Rudi’s beautiful home, a former mill house in the tiny village of Mühlbach in Kärnten, Austria. The sound of flowing water is ever present here. A retired millstone lies in the courtyard. After seven decades of grinding grain, it’s living a second life as a table. It’s doing a fine job hosting our beers as we sit below an ancient grapevine which has colonised the front of Rudi’s barn.

“It still bears grapes each autumn,” he tells me. “My neighbour picks them and makes wine.”

The name Mühlbach – means ‘Mill’s Creek’ in German – and reveals its past. But this is a Carinthian-Slovene region. Slovenian is still widely spoken by a close-knit minority and Mühlbach, like all towns and villages in the Slovene-speaking parts of Kärnten, has two names. In Slovene, the village is simply called Reka – river, suggesting it was named by Slovene speakers well before the mills appeared.

Today, Mühlbach is a sleepy settlement. With views of the snow-covered Karawanken mountains, it’s a peaceful, picturesque place; somewhere you’d come to escape the excesses of the industrial revolution. But once upon a time, it was very much part of that revolution.

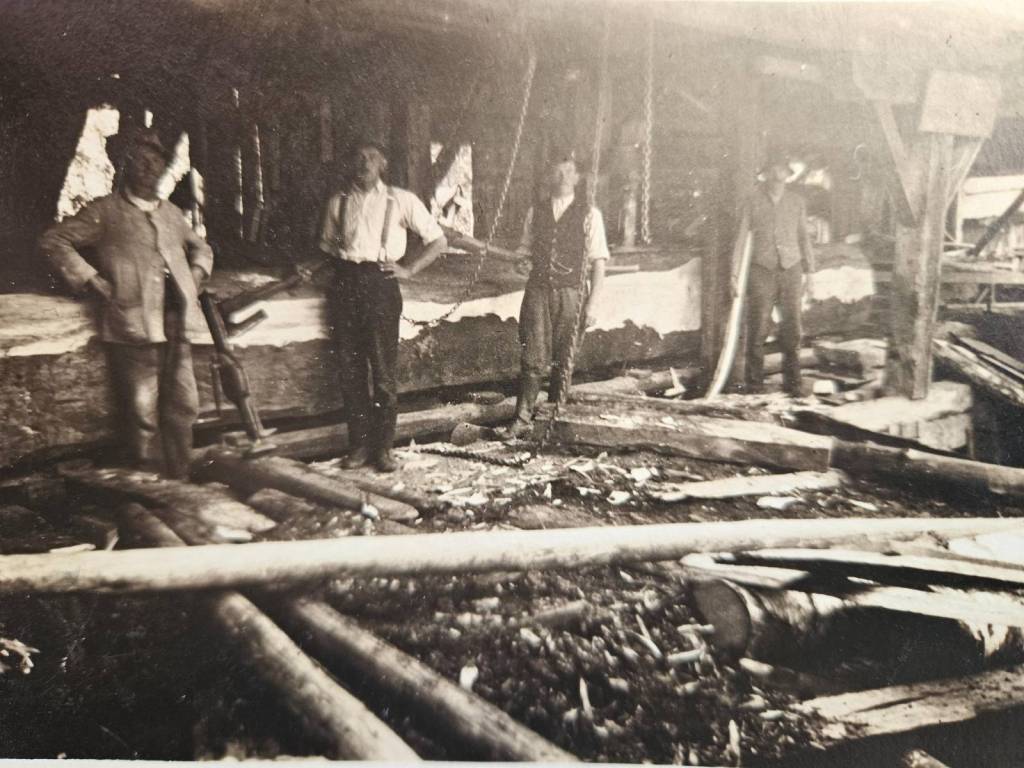

Had you visited Mühlbach in the early 1900s, you would have heard the grinding, sawing and bellowing of progress.

“There were over twenty grain mills, sawmills, blacksmiths and other workshops, all tapping the river’s energy to power their machines,” says Rudi.

Farmers delivered grain and left with flour. Timberjacks came with trunks and left with planks. It was a place people came to trade, socialise and exchange news.

The first mention of Mühlbach’s mills appear in local records around 1580. But these were just the largest ones. Rudi suspects smaller milling operations were running well before that.

I’m surprised to hear that this tranquil spot was such a hub of industrious activity. The reka is more stream than river. How could this modest channel be such a significant source of power?

“The geography here was perfect,” explains Rudi. “The way the land falls, the shape of the valley; it made it an ideal place to build a lot of mills.”

The Original SaaS Business

Rudi’s father was Austrian, his mother Croatian. But due to clashing political opinions, she was forbidden to stay in the family home, so Rudi’s parents went to live ‘in exile’ in Vorarlberg, Austria’s most westerly state.

Rudi was raised by his grandparents, who legally adopted him when he was three. He grew up in the mill house but by that time, Mühlbach’s watermill era had all but passed.

“At the start of the ‘70s, our sawmill was the only one still running. The rest had been reduced to derelict waterwheels and ruined mill races. We were forbidden from going near them but of course, we did. It was an adventure playground.”

While their farmstead provided pork, home-grown vegetables, eggs and fruit, the sawmill provided the money. It was an original SaaS business: Saw-as-a-Service.

But the waterpower was not to last. Rudi’s grandfather, Rudolph, fell out with his neighbour over the quality of the water flowing into his fish pools.

In 1979, after a long running feud, Rudolph disconnected the sawmill from the river and installed a diesel engine instead. Mühlbach’s last water-powered mill was gone.

“It was a bad decision,” says Rudi, who was eleven at the time. “The river could have provided power for three houses, but my grandfather gave up his right to use it.”

Diesel Power & The Art Space Era

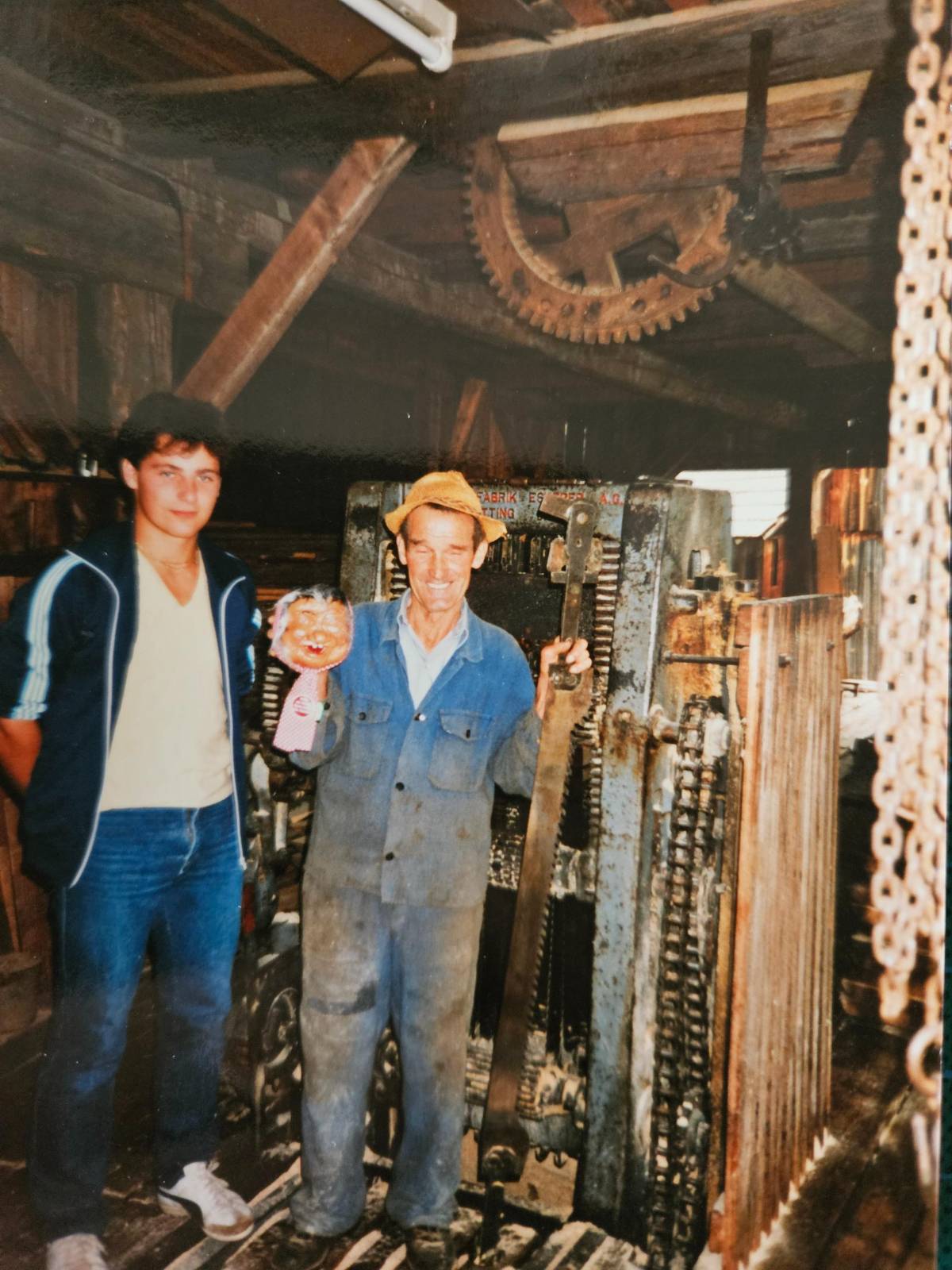

Every summer, Rudi joined his grandfather in the new diesel-powered sawmill. He learned how to move the timber, how to maintain the engine, how to saw the lumber.

They continued milling for another decade until 1988, when Rudolph retired and finally, the last mill of Mühlbach closed.

“Those last years were particularly busy,” recalls Rudi. “The building of the autobahn forced the sale of one of our best forest parcels. We had to fell the lot. I still have some planks from that time.”

With the mill closed, quiet fell upon the village. At age 80, Rudolph passed and Rudi inherited the family smallholding. For the next decade, the sawmill sat in stasis, slowly being eaten by the elements. Rudi thought about tearing it down and selling the land. But with the structure still sound, he conceived a different future.

“I decided to turn it into an art space. I cleared out all the old wood, upgraded the electricity and installed lighting. It wasn’t about money. I just wanted to provide somewhere for local artists to work, exhibit and gather. I envisioned hosting small events: music nights, readings, workshops. And we did do a few. But I was maybe a little naïve.”

Rudi’s first – and only, as it turned out – artist to set up shop in the mill was a local sculptor. But he was not a model tenant.

“Things started off ok, but then he began to fill the mill with all his personal junk. It became a complete mess. I wanted other artists to work there too, but he was taking all the room. Then the neighbours started to complain it was an eyesore. I had wanted to combine this beautiful old structure with beautiful artwork. But it didn’t work out.”

Rudi evicted the errant sculptor, (along with his junk), and shut the art space down.

The Resurrection

The question of what to do with the mill surfaced once more. Whilst pondering its future with friends one evening, the suggestion of resurrecting it for its original purpose surfaced.

“Why not see if the saw still runs?” they asked.

Rudi played with the idea. Curious to know how the saw had aged during its long years of slumber, he began examining the machinery, starting with the engine, housed in the belly of the building.

Incredibly, despite almost two decades since it last sang, Rudi succeeded in getting the engine going after just four hours of tinkering.

Next he tackled the saw.

“It was exactly one week after I had brought the engine back to life,” recalls Rudi. “By the end of the day, this machinery, which was then 101 years old, was also running again.”

It took another year fiddling with cogs, chains, bearings and blades to restore full order to the mill but in 2007, after 19 years of silence, the sound of sawing returned to Mühlbach.

“I found two old books explaining the secrets and mathematics of saw machinery. I made lots of changes and managed to get the saw cutting trunks four times faster than my grandfather. This was pure enjoyment for my scientist and engineer soul.”

A Gift To The Village

Rudi’s art space may not have worked out, but the resurrection of the mill turned out to be an art attraction in its own right. Neighbours excitedly flocked to see this living history and talk about the old times.

“I realised that running the saw was the best way to preserve it. A ritual to remember the old ways. It’s a gift to the village; the last mill of Mühlbach,” he says.

“I hosted an art performance there. A live band played – sounding like Pink Floyd – while I was running the saw mill in real-time. The noise of the engines were part of the soundscape.”

Rudi, now in his 50s, runs the saw just a few days each year – normally around Christmas time. It’s tough, physical work. Just getting the trunks into position requires significant effort; there is much heaving, hefting, rolling and lifting.

But it’s an intellectual challenge too. In a small, enclosed workshop at one end of the mill, warmed by a log stove, Rudi explains how he adjusts the kerf of each blade, sharpens each tooth, and how – with clever modifications – he optimised the saw’s efficiency.

“It takes two or three days to get the mill ready. Then I saw for a day or two. Cleaning up takes another two days. Although I use the planks that I cut, it would be cheaper to buy them! But it’s a time capsule. It’s an artistic intervention. It’s a living example that shows how much lives have changed here. And it’s very satisfying to see how much one man can accomplish. With the right tools and techniques, you can do a lot with minimal physical effort.”

Why Save The Saw?

I’m curious as to why Rudi invests so much of his energy in the mill. His answer is more complicated than I expected.

“I’m very grateful for what my grandfather passed on to me in 1993; a wonderful place, house, garden, farm and sawmill. All together seven buildings.

“It’s a time capsule. Especially because my parents’ generation was missing in the chain. Although the mill and all the tools were still functional, everything was rendered useless in these modern times. They produce no cash-flow. They were a liability.

“But I had seen all of them in action, used by my grandparents, named in the old dying Slovenian dialect. It would break my heart to throw everything away and completely destroy the last of this world.

“So, how to deal with it? One approach is artistic: rearranging/exposing/highlighting fragments, artefacts and sounds. The second one is philosophical. In the ’80s and ’90s it was already clear as day that the global economy was going mad.

“My grandfather always told me: they are out of their minds! This will not work out.

“Nowadays the whole world is talking about sustainable economies and climate friendly supply chains. And so, here we are again. The sawmill exemplifies the sustainabilty movement: it’s organic, local, regional, a sustainable scale, and satisfying.

“A friend of mine who visited the sawmill once said: Rudy, this is the most honest thing you ever did!“

The Final Cut

I’m back in the sawmill, attending one of Rudi’s sawmilling days. Open to the elements on two sides, there are metal cogs, fly wheels, pulleys and oak-handled cant hooks hanging from the walls. Lengths of heavy chain dangle from the beams.

Rudi watches the saw intently. He dives around the machinery, making adjustments as the trunk passes through the blades and on to a second set of rollers that wheel along rails that run the length of the mill. Finally, the last of the trunk is sawn. Rudi shuts off the machine and silence falls.

Though we can clearly see the trunk has been sliced into eight thick boards, it has held its form; it still looks like a tree.

“This is my very favourite part,” says Rudi.

Grabbing an iron pry bar, he gives the lumber a good, hard knock. It flops apart instantly, separating into perfect planks that fall like dominoes.

It’s in this moment that I understand why Rudi goes to such lengths to keep the mill alive. It’s as if he has cracked open a Fabergé egg. Locked inside this tree for a century, the ash’s inner treasure is now revealed; crisp, white margins flank a beautiful, swirling, inky-black grain. It would make a fine farmhouse table.

As for the saw’s future, Rudi knows it’s living out its twilight years.

“At some point, something big will break,” he says. “Either the roof, or the engine. When that happens, it’s over.”

Until then, Rudi continues to run his sawmill for a few days every year, preserving 400 years of history.

And even when Rudi’s mill makes its final cut, the timber that it transformed into such beautiful boards, beams and planks, will live on.

Indeed, wander around the villages of the Rosental today, and you might just spy Rudi’s wood as a roof, table, or bench, in the old homes and farms of the valley.

Leave a reply to Benito Aramando Cancel reply