I confess I was peeved. It was already 9:18am – eighteen minutes after opening – yet only two of the seven lifts were running. When I questioned the lifty in broken German, he mumbled something about technische problems. I supposed I shouldn’t have been surprised. On previous visits, I’d seen similar. I just thought that after nearly 50 years of operation, they would have worked out the bugs by now.

Limited to the only open lift atop the mountain – a short, button drag – I set off. My snowboard gripped the freshly raked corduroy; the edge of my Moonchild Malibu leaving just a thin, precise line behind. I painted some arcs, then made for the side of the slope, where spruce branches were loaded down with the fresh fall. Exiting the piste’s grooves, I launched on to a plump duvet of beautiful, bouncy powder.

It was only enough for a few turns; a few fleeting meters of deep, sweeping turns that left little clouds of crystals hanging in the air. But any annoyance I’d been harbouring over the technische problems evapourated instantly.

Here I was on a Thursday morning in January, surfing Carinthian powder, the slope all to myself. The sun was out, the sky was blue and there was not a breath of wind. I lapped that short, button drag until every inch of powder was spent.

Living under the mountain

Aside from the winter when I worked in Whistler, Canada – sharing a cramped bunk room with an Aussie, in a slope-side staff block – I have never lived closer to a ski lift. I’d timed the drive. I could be rumbling up the three-man chair at the base of the mountain within nine minutes of closing my front door.

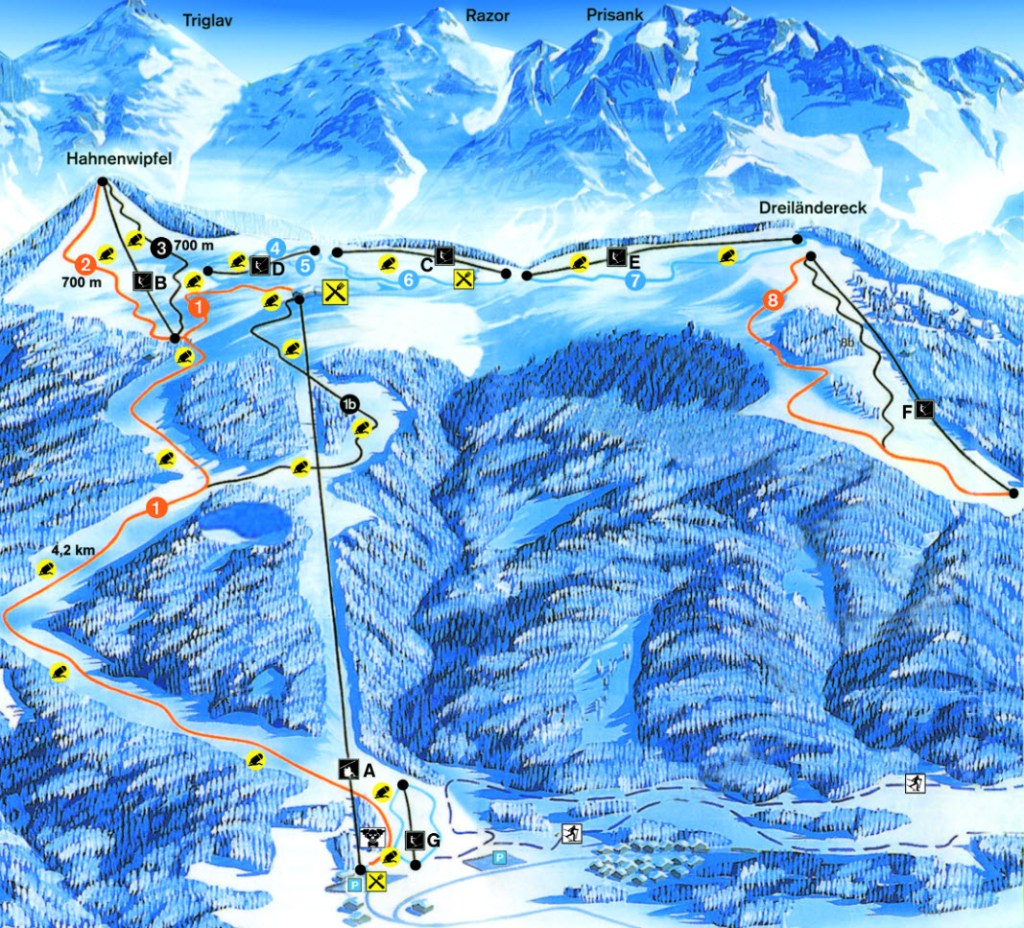

Whistler was a world-famous resort offering acres of skiing and attracting visitors from all over the globe. Dreiländereck was tiny; its high point was 1550m, it had just 870m of vertical, one chairlift, and six drags – not that I ever saw them all open at the same time.

On a really good day you might get three hours of fun. Not a place you’d fly over oceans for. But during my two-year stint in a mountainous region of backwoods Japan dotted with micro-resorts, I’d learned that size really doesn’t matter; it’s snow that counts. And when you have enough fresh, light, white stuff, even the shortest slope is pure joy.

That winter I made the most of that nine-minute ski commute. Keeping a constant eye on the snow reports, when a big fall landed, I would hit the lifts early, consuming the fresh before being back at my desk for work by mid-morning.

It had taken me twenty years of dreaming, luck, and engineering my life, to find myself living with a ski mountain on my doorstep. But finally, the boy from snow-starved rural England had landed.

Skiparadies Lost: The Decline of Dreiländereck

By the time I discovered it in the early 2020s, Dreiländereck was in decline. I knew it was in trouble; I’d heard the rumours. I just didn’t think that that glorious Thursday morning in January would be my last powder hour there.

In February 2024, the lifts closed, ending the season early. And the following winter – which would have been Dreiländereck’s 50th anniversary – they never opened at all. The death of Dreiländereck was complete.

The official reason reported by local media was: “insolvency due to financial difficulties and a decline in visitor numbers.”

Though the area – like low-lying ski resorts the world over – was suffering from warming winters and declining snowfalls, I’d suggest visitor numbers were not helped by the shoddy management. Certainly, in my experience of snowboarding Dreiländereck, the problems seemed more born of bad administration than snow scarcity.

When other ski mountains in the area had their snow cannons running full steam to capitalise on sub-zero temperatures, Dreiländereck frequently had its snow-makers off.

Important information on the website – the design of which had apparently not been refreshed since the late ’90s – was updated erratically. Sometimes I would check it to confirm the resort was open for business, only to arrive and find it inexplicably closed.

One time, I went to buy a pass but discovered the ticket office was shut. A cashier turned up 15 minutes late as a queue steadily built. Most of the lifts also opened late, if at all; one was permanently closed, cheating skiers of a fine red run and one of the few blacks.

The t-bar that served the steep slope at the back – the place to head when powder was on the menu – was open perhaps just fifty percent of the time. And even when half the lifts were closed, you still had to pay full price for a pass.

From skiparadies to barebones operation, it seemed a great shame that Dreiländereck had been so neglected. I wondered what a wonderful place it could become again, if taken over by a keen, competent team.

Dreiländereke’s Glory Days

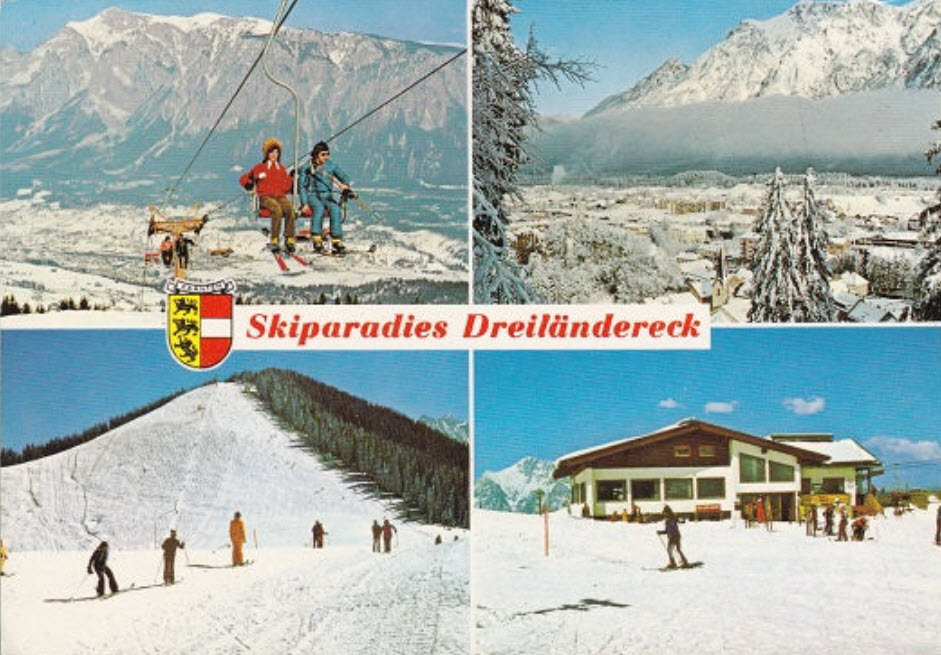

It wasn’t always like this. My in-laws told me of the Dreiländereck’s glory days during the ‘80s and ‘90s.

“It was normal to queue for a lift for an hour! But nobody minded. We were just so happy and excited to be skiing. Lift tickets were cheap, it was a place where you knew everyone. It was a way to enjoy winter.”

It’s hard for me to conceive waiting that long for a lift. But thanks to savvy marketing, during its heyday, Dreiländereck’s ‘three country ski experience’ was attracting Hungarians, Czechs and other central Europeans.

Indeed – Dreiländereck, often written as ‘3-Ländereck’ in their marketing – means ‘three countries corner’. And it’s the only border in the world where Germanic, Latin and Slavic cultures meet.

For many years, there was even the special senza confini lift pass that covered Austria’s Dreiländereck, nearby Lussari in Italy, and Kranjska Gora in Slovenia. This unique selling point would have made for an exotic ski holiday.

Hotels, pensions and restaurants sprung up around the base of the slope and in nearby Arnoldstein, catering for the booming ski business.

For locals like my wife’s family, Dreiländereck was the hausberg: the home mountain. During winter, her family spent almost every day skiing up there after school.

“We knew every centimetre of the pistes; every little shortcut through the trees, and every member of staff. It was like a family to us so our parents let us have free range on the mountain.”

Later, my wife worked at Dreiländereck as a ski instructor during her 20s, as did her brother, as had their mother, and their grandmother.

But by the twenty-teens, those hour-long queues of paying skiers had dissapeared. And with those lucrative days behind it, management no longer seemed to care much for its customers.

A lament to the local ski area

In Decemeber 2024, I hiked up the now closed and quiet slope, the day after a light fall of snow, to inspect the conditions. As I took in the soft silence, it occurred to me that perhaps we shouldn’t lament the closure of ski areas. Afterall, they are significant blights on the landscape.

Great swathes of spruce, pine, beech and birch would have been floored to make way for pistes and lift pylons. Huge concrete stanchions were set to support the infrastructure. Snow cannons (when they were running) hissed at high pressure, slurping up natural water supplies.

Lost gloves, broken poles, discarded coke cans and manner schnitten wrappers appeared each spring after the thaw, littering the landscape. And all in the name of fun.

Yet lament Dreiländereck’s closure I do. Despite the less-than-perfect management, having a ski lift nine minutes away was a rare joy. It was a fast escape to snow country; a place where happiness could be inhaled on a powder day – if only for an hour.

Will Dreiländereck’s ski lifts ever open again?

Dreiländereck’s future as a ski area now hangs precariously. To know if it could rise again, we’d need to know why it fell. And that’s where the story gets murky.

Kranjska Gora, just a 25 minute drive over the mountains into Slovenia, has only half the vertical drop of Dreiländereck’s and a high point 500m lower, yet it is thriving. Italy’s Lussari, also part of the original tri-border alliance, remains very popular as well. So being a small area at low altitude cannot be the only excuse for Dreiländereck’s downfall.

Local rumours suggest other reasons: lack of suitable investors, lack of cooperation from the council, lack of funds from the government, lack of agreement between the dozens of landowners, and lack of desire by the owner to keep it running. There are whisperings of tax dodges and under the table deals. Everyone has a different angle on it. I doubt we’ll ever know the full story.

An Off-Piste Future?

All is not lost though. Despite the lifts being closed, the Dreiländereck Hütte, a cosy mountain inn serving cold cuts, cold beer and hot, hearty regional dishes, remains open – when the snow is on. And a skeleton crew is still grooming one slope, giving ski tourers some prepared piste to schuss.

I’d love for Dreiländereck to return; to be taken over and run with the love and expertise it deserves. Hell, I’d even throw my hat into the ring and join the team if they’d have me. Being able to grab my board and thrash out a couple of powder runs on a bluebird day before work was a dream for me. And for raising the next generation of little skiers, it was ideal.

I fear, however, that it’s unlikely. So many small ski areas around the world are meeting a similar fate. Perhaps competent management and some investment could make Dreiländereck prosperous and profitable for another decade or so. But even the very best team can’t fight warming winters forever.

I’ll miss that nine-minute commute.

Leave a reply to Chief Editor Cancel reply